Christiane’s Gift

a repost from 2012

This piece was originally published on a personal blog that’s been, well, abandoned. Its original name was “Better Wings,” and its “about” menu contained a Kubrick quote I’d come to love …

“… I've never been certain whether the moral of the Icarus story should only be, as is generally accepted, ‘don't try to fly too high,’ or whether it might also be thought of as ‘forget the wax and feathers, and do a better job on the wings.’” Hence the opening lines …

If you’ve visited the “About” menu (hey, why not give it a shot) you’ll have noted that my blog derives its name from a quote by Stanley Kubrick. The late director has been one of my principal heroes since I was thirteen years old and saw 2001: A Space Odyssey in its first run at the Seattle Cinerama. Back then, Cinerama was the real thing, massive curved screen and all; a modern-day temple to the glories of cinema.

One afternoon in August of 1968, I was at the dentist’s office awaiting my turn in the big chair, thumbing through a copy of Life magazine. I turned the page, and the most remarkable sequence of images I’d ever encountered sprang out at me. Life had run a photo essay on Kubrick’s upcoming movie, and I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. This was still nearly a decade before Star Wars hit the planet, and nothing like these pictures had ever been captured on film. I already loved writer Arthur C. Clarke, and the vistas I was seeing on the pages seemed to have made a direct leap from his imagination into reality.

I immediately began the protracted ritual of begging for my parents’ promise to get me to the theater once the movie opened. My family lived across the lake from Seattle in Bellevue, which was then a quiet little Boeing suburb. It would be a really big deal for my dad to take me all the way into the city for a movie, but since malls and multiplexes hadn’t yet come into existence, there was no other option.

I’m overstating the issue; my parents were the caring sort who would always do their best to help when they knew something mattered to me. So the moment finally arrived when – after a hard day at work – my dad put his suit jacket back on, had me dress up in the same clothes I was required to wear to church (shudder – clip-on tie included) and off we went in his little beige Volkswagen beetle for a Very Grown-Up Evening of film entertainment.

The specifics of that screening are best saved for a future post. For now, I’ll state simply that the night’s sublime adventure remains, in truth, the second most significant experience of my entire life.*

From that day onward, Stanley Kubrick was in my eyes the Man, and I sought out and devoured his work and every scrap of related information I could find. I’m hardly alone in that obsession; it’s a source of great satisfaction that his legacy continues to grow with each passing year, and with each new generation of filmgoers to discover his oeuvre.

Time passed. In 1999, while audiences eagerly awaited the release of Eyes Wide Shut, news of Kubrick’s sudden death dismayed the world. The sole consolation was that mere hours earlier, Kubrick had shown his final edit to the primary cast and studio executives. His work was done.

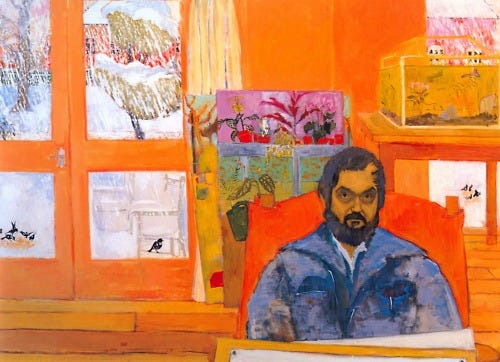

The following week, the Sunday Boston Globe ran a lead article on Kubrick’s life and achievements. It featured an image I’d never seen before: a crop of a portrait by Christiane Kubrick, his wife of forty-one years. It was beautiful; slightly impressionistic, in bold colors, with something of Mona Lisa’s ambiguity as he gazes out at the viewer with a look of – it’s hard to say – expectation? As if he’s about to ask “Well – what have you got to show me?”

A quick visit to the Interwebs located a collection of her paintings; out of print, but still available second-hand. I placed the order, and soon afterward was marveling at the quality of her work. She was clearly a skilled and self-actualized artist who would – alas – forever be pigeonholed as “Mrs. Kubrick.” Not the worst fate, and one that she was undoubtedly aware of from the very beginning; still, it’s regrettable to see an individual with so much talent consigned to living in someone else’s shadow. I imagine she made her peace with that long ago; she and her work thrive, even as “the woman behind the man.”

I faced a dilemma. I desperately wanted to remove the page with her painting of Stanley from the book and have it framed; at the same time, I resisted the idea of destroying both the integrity of the book, and the artist’s intentions for the collection. I really wanted to have that fantastic image as part of my living space, but in the end, the book remained intact – an all-too-rare instance of self-denial. It’s important for the sake of our narrative to note that I waged an exhaustive battle with my conscience; the usual tiny cartoon angel and devil hovering over each shoulder, reciting their respective advice into one ear, then the other. Back and forth, yin and yang. Little Miss Whitefeathers emerged victorious, at least for this round.

Again, time passed. At some point in the autumn of 2003, I read that the Deutsches Filmmuseum and Deutsches Architektur Museum in Frankfurt were combining to schedule the first exhibit of material from Kubrick’s personal archives. I lit up like a xenon projector bulb. I knew without question that I had to be there. No matter what it took, I would make it happen.

The fact is, once you commit yourself, these things tend to work out. Plane fare wasn’t the issue; finding an safe, affordable place to stay for nearly a week in Frankfurt was the true challenge. Again, the Internet came to the rescue. I found a network that placed tourists with property owners, who then rented space at very reasonable prices. They introduced me to a friendly chiropractor who kept a spacious room her patients could occupy during treatment; I reserved five nights in a good neighborhood for less than just one night would have cost at the downtown palaces that service fat-cat bankers. It was right beside a train stop, to boot.

Spring of 2004 found me soaring eastward in a Pratt & Whitney-powered 747. It had been many years since I crossed the Atlantic, the last trip being in 1978, when I paid a Christmas visit to my parents in Tehran, Iran. (At this point, you know the drill – grist for a future post.) Arriving in Frankfurt, I greeted my landlady (a kind person; I left her a bottle of Clicquot), settled in, and stepped out for my first meal in Germany. Then back to bed early, resolving to get a solid night’s sleep so I’d be fresh and clear the next morning.

After a quick breakfast – I have a vague memory of some extraordinary pastries – I set out for the museums. Not ready to explore the train system, I hailed a cab and was treated, with my full consent and appreciation, to a scenic tour of the city. I remember the beautiful Frankfurt skyline, the river Main passing through the city, the giant Euro symbol outside the European Central Bank … the city had an indefinable patina that only the centuries can bring. The taxi driver was very friendly and spoke impeccable English. I apologized for America’s failure to elect a more sentient leader than George W. Bush, and offered reassurance that not all Americans were jingoistic halfwits. He gave a rueful nod, observing that he and his countrymen had considerable historical experience and were well able to empathize.

Arriving at the museums, I took a moment to drink it all in.

I was struck by the fact cultural life seemed a vibrant, vital part of the city itself, to a much greater extent than I’m used to seeing in America. Everywhere were galleries, museums, colorful posters announcing events, people milling about, taking in the sights and enjoying life in the open air. Giant banners on the Filmmuseum itself displayed scenes from Kubrick films, including the notably prominent breasts of Lucy, one of the drug-dispensing mannequins from the Korova Milk Bar in A Clockwork Orange. I experienced a pang of annoyance with American culture and felt frustrated with our parochial nature, knowing that such a banner could elicit a national scandal if displayed on a museum back home. Remember how Rudy Giuliani made hay out of Piss Christ?

I’m not going to attempt to document all I saw there; there are far better resources available, notably Alison Castle’s The Stanley Kubrick Archives, which I recommend with enthusiasm. Encountering just one of these prizes on its own merits would leave any devotee agog; seeing so many at once, in such close proximity, induced a kind of euphoric sensory overload that had me approaching a state of rapture. Imagine coming in contact with the actual Star Child from 2001, complete with actor Keir Dullea’s eyes and facial bone structure, colored from end-to-end an inexplicable pastel shade of baby blue and still bearing the unmistakable residue of gaffer’s tape – barely out of camera range – on the crown of its head. That’s just one memory out of hundreds.

I moved through the exhibits at a contemplative rate, as a gourmand might pace himself during a multi-course dinner; always focusing on the serving that was in front of me, savoring it to the fullest possible degree, giving no thought to what was yet to come. Individuals and groups drifted past me, eager for the next attraction, but I was greeting old friends – icons that had been part of my life for decades, even though I’d never met them face to face. Those, and still other marvels; productions planned but unrealized, leaving the artifacts of a searing and omnivorous intellect strewn about like spiral shells sparkling on a beach.

At last I came to a series of exhibits whose utility had outlived Kubrick himself: several artists’ exploratory production drawings for A.I. Artificial Intelligence, the project Steven Spielberg brought to realization after Stanley’s death. I felt a certain melancholy, knowing the mission that had consumed me for months was coming to an end. I still had days to spend in Frankfurt, but this was the main event, the grail that had brought me across the ocean; as fulfilling as it had been, the knowledge that it was completed left me with the sensation I was drifting, unanchored.

I moved past the final row of drawings and through a doorway that opened on a hall leading to my right. Further down the hall, I could see bright sunlight and the glass panels of the entrance to the Architektur Museum. I had passed completely through the conjoined museums, and had reached the exit to the outside world. I was nowhere near ready to take those last steps; I decided I would retrace my path through the exhibits, bidding my farewell to the wonders that had drawn me there with irresistable strength.

I turned to my left, already beginning to move forward. In an instant, I froze in place; for there in a shallow alcove, unseen to the left of the doorway I’d just passed through, was the painting I had spared and left intact in my book: Christiane’s portrait of Stanley, radiating a warm, embracing burst of color that bloomed in contrast to the cool white of the hallway.

It was huge; much larger than I had imagined. I moved closer, soaking up a richness of detail that had been invisible on the printed page. Standing only a meter away, I felt the presence of both Christiane and Stanley, and was overwhelmed with emotion. There was a powerful sense of their intimacy, of the moments she spent focused on the act of painting, of the rarity of his indulgence in inactivity while sitting for her. I glimpsed echoes of the painting’s pandimensional space/time stream fluttering around me, as my usual orientation in life’s timeflow became unstuck – à la Billy Pilgrim – and jounced around on its pivots, casting luminous, shimmering layers of visions of the private lives the painting had witnessed.

There was a low bench against the wall to my right. I sat, gazed, and shared space with her art, alone and uninterrupted by other patrons. Not a single person came within my sight during the entire time I sat there. I wondered; out of all the people who were visiting the exhibit – and there were crowds – how few had chanced around this corner, and paused to comprehend the true nature of the gift Christiane was sharing? How many had appreciated her heart and generosity, her faith in the good nature of the myriad strangers to whom she had granted access to this, among the most precious and irreplaceable of personal treasures?

Sometimes it’s enough that a single observer is there to see and know. Whether I had realized it or not, I had embarked on a pilgrimage; to show gratitude, to pay my last respects to a man who ignited a fire in our consciousness that blazes on through our lives and culture. I rose, and moved unseeing past the reverse chronology of the exhibits, my mind absorbed by a reward I never expected the journey could bestow. Emerging from the Filmmuseum’s entrance, I stepped blinking into the bright Frankfurt day, the unexplored city offering its streets in airy invitation.

*As Patrick McGoohan had a habit of asking, “Who is Number One?” That story, patient reader, will also be saved for a future post.

Thank you so much for sharing this. Beautifully written